A cultural crossroad sits at the intersection of horsepower and harmony, where instrument panels glow as brightly as the stage lights and lyrics race along like a highway at dusk. From the dawn of automotive popular culture in the mid-20th century through the rock and folk revolutions that followed, car imagery has repeatedly served as a powerful lens for storytelling in music. This feature examines seven quintessential car songs that stand out for how they celebrated, challenged, and crystallized the era’s car culture. Beyond the Beach Boys, the lineup spans Janis Joplin, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Ronny and the Daytonas, Johnny Cash, and Jan and Dean, each track offering a distinctive tale about machines, road myths, and American identity. The broader backdrop is the era when cars didn’t merely transport people; they defined youth, freedom, rebellion, and aspiration, often in tandem with hot-rodded engines and the roar of the open road. It’s a period when the muscle car era and the explosion of rock ’n’ roll seemed to rise in parallel, each fueling the other. And within that landscape, a few records became touchstones—not merely songs about automobiles, but songs about what cars stood for in the public imagination.

The Beach Boys and the car-song boom: Little Deuce Coupe and Fun Fun Fun

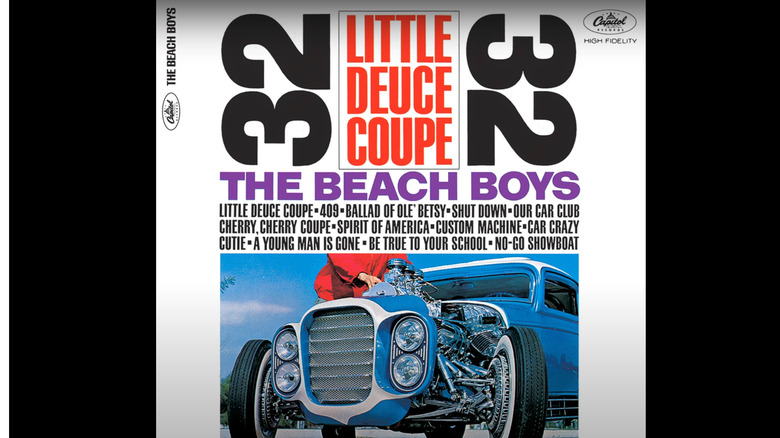

The early 1960s marked a flourishing intersection of American automotive design and popular music, a moment when car culture and rock ’n’ roll collided in a way that reshaped both industries. The Beach Boys stood at the heart of this convergence, and their 1963 album Little Deuce Coupe became a cornerstone in the car-song canon. The collection is saturated with motor-reference storytelling, celebrating chrome and speed while capturing the anxieties and fantasies of a generation enamored with the open road. The album itself achieved notable chart success, rising to the top tier of the Billboard 200 and spending a substantial stretch in the upper echelon, a testament to how deeply listeners connected with the vicarious thrills of American car culture.

Among the album’s standout tracks, the title cut “Little Deuce Coupe” epitomizes the era’s fascination with hot rods and automotive identity. The song’s very premise centers on a car as much as a character, a symbol of youth, customization, and the feverish energy of cruising. It’s a sentiment that was already echoing across the nation as car culture moved from a hobby into a lifestyle for millions. If the album’s broader arc celebrated the romance of the open road, its follow-up material further captured the tempo and tempo of cruising life. In particular, one track that would resonate deeply with audiences is “Fun Fun Fun.” Created and recorded as a rapid-fire, upbeat response to the car-centered storytelling of the era, “Fun Fun Fun” tells the story of a young woman who tears through the streets in her father’s Ford Thunderbird, living fast until her father uncovers her escapades and confiscates her keys.

That Thunderbird, a first-generation model, holds a storied place in American automotive design history for its distinctive styling and cultural resonance. The car’s sleek lines and aspirational aura made it emblematic of urban adolescence and the dream of personal freedom. It’s noteworthy that the album cover’s imagery seems to echo that same aura: while the song centers on a Thunderbird, the visual framing shows the band leaning on a Chevy Corvette and what appears to be a Pontiac GTO, underscoring the era’s fusion of cross-brand performance icons and car culture’s visual lexicon. This deliberate juxtaposition reflects how the music and the cars of the time were part of a shared mythos—one where the vehicle is as much a mood as a machine.

“Fun Fun Fun” has endured in the Beach Boys’ live repertoire well beyond the 1960s, extending its appeal to contemporary audiences and remaining a touchstone of the band’s legacy as a driving force in early rock-infused auto storytelling. The chorus—“she’ll have fun, fun, fun till her daddy takes the T-bird away”—has become a cultural shorthand for youthful rebellion tempered by parental boundaries, a dynamic that remains deeply relatable across generations. The song’s lines conjure vivid snapshots of mid-20th-century cruising culture, with references that evoke hamburger stands, highway traffic, and impromptu street races, all of which helped anchor the track in a specific moment in American life. The broader impact of the Beach Boys’ car songs lies not simply in the melodies or the production but in how they codified a social milieu—the ritual of the drive, the culture of the drive-in, and the social rituals that grew around the automobile as a space for companionship, risk, and identity formation.

This era’s car songs were more than entertainment; they were a mirror reflecting the era’s optimism and trepidation. The Beach Boys’ work exemplified a seamless blend of catchiness and cultural commentary, turning a vehicle into a narrative engine that propelled stories of romance, rebellion, social customs, and the status of youth in a rapidly changing United States. While other artists would soon contribute to the car-song genre with different tonal timbres—rock, folk, and eventually hip-hop—the Beach Boys’ car-centric storytelling laid a durable groundwork that would influence subsequent generations of writers and performers. Their musical experiments around cars weren’t just about the thrill of the ride; they were about the culture that the ride carried with it: the communal rituals of fuel, fragrance of exhaust, the glow of neon signs at night, and the possibility of escape that a long highway often promises.

Delving into “Fun Fun Fun” reveals more than a simple pop tune. It presents a microcosm of the broader American car culture: the teenager’s desire, the parental boundary, the social rituals around driving, and the archetype of the car as a character in its own right. The song’s enduring appeal comes from its buoyant tempo, playful storytelling, and the way it translates a drive into a theatrical moment. Listeners can hear the street scenes in the verses, feel the momentum in the chorus, and sense the warm nostalgia of a period when a road trip could be a life-changing event. The track’s endurance is also a testament to the Beach Boys’ craftsmanship in blending harmony-driven pop with road-ready storytelling—themes that would echo in countless songs for years to come, as other artists found their own ways to celebrate cars while using them to probe love, ambition, and the American dream.

In a broader sense, “Fun Fun Fun” and the Little Deuce Coupe era capture a crucial cultural pivot: cars were no longer just modes of transportation; they became moving stages for youth culture, social performance, and personal identity. The Beach Boys’ success with car-themed material, including the album’s other car-centered tracks, demonstrated how music could translate car culture’s sensory and social components into a universal language. The result was a sonic landscape that celebrated speed and style while also acknowledging the boundaries and consequences that accompanied such privilege. The legacy of this moment—when a Thunderbird could symbolize rebellion, a Chevy Corvette could serve as a backdrop to a social tableau, and a rock band could make a car into a storytelling partner—still informs how we understand car songs today. It is this layered richness—the accumulation of myth, memory, and musical craft—that elevates the Beach Boys’ car songs from novelty tunes to enduring cultural artifacts.

Mercedes Benz by Janis Joplin: an origin story that transcends car worship

Among the most remarkable car-adjacent songs in modern music is Janis Joplin’s stark, acapella moment, “Mercedes Benz.” Its origin story is as combustible and improvisational as the performance that birthed it. One August night in 1970, at Vahsen’s bar in Port Chester, New York, Joplin sat with Bob Neuwirth, a folk luminary in his own right, along with actors Geraldine Page and Rip Torn. The line “C’mon God, and buy me a Mercedes-Benz” wasn’t a premeditated lyric; it emerged during a spontaneous riff sparked by a line belonging to Beat poet Michael McClure. McClure, fiddling with an autoharp—an instrument provided by Bob Dylan—spooled out the original thought, and Joplin and Neuwirth quickly reshaped that line into a haunting, minimalist performance. Neuwirth reportedly scribbled the resulting lyric on bar napkins in the moment, a tangible record of the song’s serendipitous genesis. A short time later, Joplin stunned her band by delivering an a cappella rendition that captured the room’s breathless attention just hours afterward at Capitol Theatre, across town. The anecdote about the performance underscores how improvisation and vulnerability can yield enduring art, particularly when a songwriter’s voice is as iconic as Joplin’s.

It is noteworthy that the track’s title does not carry a hyphen in its official spelling, while the car brand—Mercedes-Benz—employs the hyphen. The juxtaposition of style and substance in the lyric’s punchline—a blunt, rhetorical appeal for luxury and escape—evokes a pointed critique of materialism rather than a celebration of a brand’s prestige. Joplin’s decision to record the song toward the tail end of the Pearl album’s sessions, and the timing of her death just a few days later, lend the ballad a poignant afterglow: the piece became a final, unblemished expression of longing and irony, a stark counterpoint to the more expansive suites of the Pearl era. The broader narrative told by this song moves beyond its car-centered image; it serves as a meditation on desire, the perils of consumer excess, and the existential hunger that can accompany fame.

The artistic intent behind Mercedes Benz stands apart from the more celebratory car anthems that populate other tracks in car-song anthologies. Rather than admiring a particular vehicle or prosaically extolling the thrill of speed, Joplin’s performance places the listener at the edge of satire and spirituality, opening a window onto questions about what money can or cannot buy, and whether luxurious possessions can substitute for human connection or moral clarity. The acapella delivery intensifies this critique, because it strips away accompaniment and ornamentation, leaving the raw request and the rawness of longing exposed for listeners to weigh. The song’s stark minimalism invites listeners to consider the emptiness that can accompany material wealth, while also acknowledging the unavoidable human impulse toward transcendence and longing for a life that feels rich in meaning.

The track’s cultural resonance is inseparable from Joplin’s legacy as an artist who used her voice to tilt against complacency, and it resonates today as a provocative, intimate portrait of desire, impermanence, and the fragile romance of consumption. The backstory—born in a bar session, crystallized on napkins, and performed in an intimate setting—illustrates how ephemeral moments can crystallize into enduring works of art when they capture something essential about the era’s social mood. The song’s place within the broader Pearl era adds to its gravity: a late-in-the-game creation that underscores Joplin’s unflinching willingness to push boundaries and to explore the tension between material longing and spiritual need. It remains a stark reminder that in the car culture’s musical imagination, the vehicle is indeed a vehicle for questions about life, happiness, and what we truly value.

Mercedes Benz, then, occupies a singular niche in the car-song canon—a composition that exists not to praise a particular mode of transport but to critique and illuminate a more universal hunger. It serves as a counterpoint within a catalog that often leans toward celebration and fetishization of speed, luxury, and mechanical prowess. By foregrounding a raw, unaccompanied vocal performance that centers on desire rather than driving dynamics, Joplin’s piece expands the emotional and thematic spectrum of car songs, demonstrating how the relationship between people and machines can be both intimate and dissonant. The origin story surrounding the track—from a bar napkin to a studio performance to a posthumous release—adds to its aura as a mythic artifact of rock history: a moment of improvisational fermentation that became an enduring meditation on yearning, money, and the elusive possibility of buying happiness.

Prince’s Little Red Corvette: a metaphor with a pink Mercury Montclair

Prince’s “Little Red Corvette” shows how car imagery can function as a layered metaphor, with the vehicle serving as a symbol for virility, desire, and the complexities of romance rather than simply being a portrait of a specific model. The song’s origins sit at the intersection of personal memory and sonic invention, with a vivid anecdote about how the seed for the track sprang to life in the back seat of a car during a moment of intimate tension. Keyboardist Lisa Coleman, a longtime collaborator with Prince and a member of The Revolution, recalled that the inspiration for the song emerged in the back seat of a pink and white 1964 Mercury Montclair. Coleman explained that the scene likely involved two people in a moment of closeness, and that the “seed” of the idea may have arrived during a moment of post-coital reflection. Crucially, the story clarifies that the inspiration did not involve a red Corvette as the titular image might suggest; rather, the car that prompted the spark was a pink Mercury Montclair. This distinction matters for understanding the track’s symbolic architecture: the color mismatch between the title and the actual car underscores the broader idea that the song’s metaphorical engine runs on mood, desire, and social signals rather than a literal automotive object.

First released on Prince’s 1982 album 1999, “Little Red Corvette” quickly became a staple of his catalog, later appearing on multiple anthology and greatest-hits collections. A close reading of the lyrics reveals that the track is as much about romance, risk, and the precarious dynamics of desire as it is about a car. Critics and listeners have often debated the exact meaning behind the carrion imagery of speed and danger within the lyrics, but the broader interpretation emphasizes how the car in this song operates as a symbol for sexual conquest, urgency, and the transience of youthful flirtation. The metaphor’s potency lies in its subversion: even though a high-performance vehicle might evoke power and control, the song ultimately reveals vulnerabilities and the limits of one’s ability to manage the consequences of new romantic entanglements.

The track’s sonic texture—lush, synthesizer-driven arrangements, punchy percussion, and Prince’s signature blend of sensuality with pop sophistication—helps convey the dual nature of speed as attraction and risk. The song’s arrangement, like its narrative, walks a line between exhilaration and peril, inviting listeners to consider how risk-taking in love functions much like the risk-taking of driving a powerful car. The broader cultural resonance of the track lies in its critique of the dating culture and the performative aspects of pursuit in the early 1980s, when speed and spectacle were central to fashion, media representation, and social signaling. The final iteration of the song—whether encountered in the context of the 1999 era or in later reissues—continues to highlight Prince’s talent for turning everyday objects into potent, multi-layered metaphorical devices.

The story behind Little Red Corvette also reframes the car itself as a social instrument: not merely a machine that conveys people from place to place, but a conduit that amplifies desire and risk, exposing the fragility of relationships under the glare of performance and perception. In this sense, Prince’s track stands apart from more celebratory car songs: its acceleration toward romantic escalation and the ensuing hours of consequence form a narrative arc that echoes broader themes in Prince’s work—identity, sexuality, and the complex interplay between personal agency and social expectation. The pink Mercury Montclair anecdote adds a humanizing, backstage element to the song’s mythos, reminding us that the origins of a timeless track often hide in ordinary moments and everyday settings, where a car’s interior or a late-night conversation can spark a cultural classic.

Cadillac Ranch: Bruce Springsteen’s ode to cars, dreams, and the American road

Bruce Springsteen’s catalog includes multiple songs that treat cars as vehicles for freedom, possibility, and vigilant social commentary. Among them, Cadillac Ranch stands out as a high-energy tribute to the car as a symbol of American myth, aspiration, and escape. The track sits within The River era, a period when Springsteen used his sprawling double album to explore the tensions between mobility, work, love, and the longings that fuel everyday life. The car imagery—the Eldorado fins, whitewalls, and skirts—evokes classic American automobiles and the glamour associated with mid-20th-century road culture, while also indexing a broader cultural conversation about how cars function as markers of status and identity in postwar America.

The Cadillac Ranch itself is an iconic roadside sculpture just outside Amarillo, Texas, where ten Cadillacs are buried nose-first in the desert, their chrome mables and tailfins pointing toward the sky. Commissioned in 1974 by the artist Stanley Marsh 3, the installation uses the stark, surreal image of cars half-submerged in the earth to comment on American consumerism, the pursuit of wealth, and the idea of the “american dream” as something both dazzling and precarious. Marsh’s decision to use an Arabic numeral in his name—rather than the Roman numeral—was a deliberate rejection of pretentiousness, signaling a desire to present the work as accessible and unromantic in its core message. In conversations with The New York Times decades later, Marsh described the Cadillac Ranch as “a monument to the American dream,” a description that captures the complex triangulation between the glamour of car culture and the more pragmatic yearnings of adolescence and youth. For Springsteen, the Cadillac Ranch becomes a lyric-stage upon which the broader themes of his work—freedom, risk, and the consequences of chasing a dream—unfold with kinetic energy and social commentary.

The song’s lyrics weave the car as a symbol of possibility with the broader social landscape of the era. The imagery of “Eldorado fins” and the “whitewalls” conjures a world where cars are not only mechanical companions but also canvases upon which visions of mobility, sex, and status are painted. The line between the vehicle and the social theater through which it moves grows thin, revealing how the road becomes a space where personal aspiration collides with societal expectations, economic realities, and the friction of daily life. The track’s electric rhythm and ebullient guitar work mirror the sense of driving that characterizes so much of Springsteen’s work: the urge to move forward, to escape, to reinvent oneself, and to navigate the rough edges of a world that often makes that journey difficult.

Cadillac Ranch’s cultural resonance is deepened by its real-world connections—the installation’s evolution, the discussions it has sparked about urban-rural divides, and the way it embodies a tactile reminder of the American dream’s grandeur and fragility. For fans of car songs, the track offers a potent blend of car-sourced imagery, myth-making, and social reflection. The car is not merely a prop; it is a living symbol that carries the weight of the nation’s hopes and the friction of lived experience. In Springsteen’s hands, Cadillac Ranch becomes an anthem about the restless energy that drives us to explore, to dream bigger, and to reckon with the choices and consequences that come with chasing after something as alluring and as perilous as the open road.

The broader implication of Cadillac Ranch in the car-song canon is its insistence on a social dimension to the romance of speed. It’s easy to romanticize the mobility that cars represent, but Springsteen’s portrayal invites listeners to interrogate that symbolism and to acknowledge how the road becomes a stage for both personal transformation and social critique. The track is emblematic of a larger tradition in which the car is a site where memory and desire collide with economic and cultural realities, producing a music that captures not only the thrill of the ride but the ethical weight of chasing the dream in a country where opportunity has always walked a line with inequality. In that sense, Cadillac Ranch is more than a tune; it is a compact social panorama—a snapshot of an era that celebrated mobility while examining its consequences against the backdrop of America’s evolving landscape.

The Pontiac GTO and the birth of the muscle-car anthem

The Pontiac GTO’s arrival in 1964 marked a watershed moment in American automotive culture and popular music’s relationship to the era’s most legendary cars. Designed in the hands of John DeLorean, the GTO quickly earned a reputation as a powerful, performance-focused machine that would help catalyze the muscle car era. The car’s breakthrough status sparked a rapid cultural feedback loop: songs about high-performance hardware followed, and then those tunes reinforced the mythos surrounding the car’s capabilities, aesthetic, and social appeal.

The song most closely associated with the GTO is Ronny and the Daytonas’ “G.T.O.,” released in 1964. The track is frequently misnamed as “Little GTO” due to its opening line, which addresses the vehicle directly. It was the Daytonas’ debut single, quickly climbing to No. 4 on Billboard’s Pop Singles chart and eventually selling more than a million copies. The success of the song helped to cement the Pontiac GTO as a symbol of automotive prestige and power, and it contributed to the broader cultural imagination around the era’s performance cars.

The car described in the song—an upgraded, tri-powered 389 cubic inch V8 with a hot cam and performance exhaust—became a shorthand for speed, engineering prowess, and the allure of the street race as a form of social currency. The GTO’s crown as a proto-muscle car is inseparable from its role in a musical narrative that celebrated speed and the thrill of the road, while also signaling a shift in the automotive industry toward high-performance models targeted at younger buyers seeking a sense of control and domination on the open street.

The broader story behind the GTO’s musical fame is deeply intertwined with the work and influence of those who shaped the era’s music industry and songwriting culture. The composer Ronny Wilkin—who sometimes was cataloged under the stage name Ronny and the Daytonas—worked with a musical ecosystem that included his mother, Marijohn Wilkin, a celebrated songwriter who would later be inducted into both the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Country Music Hall of Fame. Marijohn established Buckhorn Music to publish her son’s song in 1964, and the following year she brought Kris Kristofferson on as a writer for the venture. The elder Wilkin’s imprint on the publishing world—and the family’s broader engagement with the music industry—helped to foster a creative environment that supported the development of a generation of writers who would go on to shape the country and pop landscapes in the years that followed. The collaboration of talent, from the young Wilkin and his guitar-driven vehicle song to the mentoring and publishing support from Marijohn, underscores the ecosystem that nurtured automotive-themed music during this era.

The cultural significance of the Pontiac GTO and its associated songs extends beyond the scale of a single track. The phenomenon helped to cultivate a broader fascination with high-performance vehicles as cultural icons, a fascination that carried into the 1960s and beyond. The GTO’s musical legacy is thus inseparable from the wider muscle car narrative, a narrative that placed American engineering ingenuity alongside expressive artistic output. The car’s symbolic value—speed, power, wealth, masculinity—became a potent fusion point for music and automotive culture, reinforcing a sense of youth liberation while also highlighting the social and economic dynamics of the period. The GTO’s presence in song, therefore, stands as a microcosm of a broader cultural shift: vehicles and songs together helped to define a generation’s sense of possibility, risk, and the thrill of chasing a dream at street level.

Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time: larceny on a grand scale, an all-American Frankenstein

Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time is a quintessential example of how a car-themed song can function as a playful, satirical, and morally instructive story about the American dream gone awry. The tale centers on a factory line worker who, with a mischievous streak, recruits a cadre of accomplices—friends and colleagues—by carrying small, seemingly harmless items out of the Cadillac assembly line to assemble a “FrankenCadillac.” The fictional conceit plays out as a clever, lighthearted heist narrative that spans multiple years and culminates in a car assembled from mismatched parts across years and models. The song’s humor is anchored by the absurdity of the heist: three headlights, one tailfin, a title that weighs in at 60 pounds—an assemblage that should be comically impossible, yet somehow becomes a testament to a craving for a singular, personalized dream.

Two versions of the FrankenCadillac emerged from real-world efforts to bring the concept to life in a broader promotional context. The first was undertaken by a Nashville salvage yard proprietor named Bruce Fitzpatrick, who built a FrankenCadillac for a promotional tour; that car was eventually destroyed after serving its purpose. The second, conducted by Oklahoma’s Bill Patch, was designed to raise funds for a local Lion’s Club chapter. In Cash’s view, the car’s creation was a testament to the showman’s art and the song’s sense of humorous mischief, and the artist even traveled to Welch, Oklahoma, to perform a concert series to honor Patch’s work. The FrankenCadillac’s significance lies not merely in its novelty value but in its embodiment of Cash’s antiestablishment stance and his affinity for the character that is the outlaw or maverick in American culture—someone who rewrites the rules, even if only in a car-themed fantasy.

The story of the FrankenCadillac coincides with a broader real-world curiosity about the ways in which cars can be poetic and symbolic. The repeated attempts to realize the concept in tangible form—a car built out of parts from different eras—illustrate how a song can inspire physical creations that extend its narrative beyond the studio and into the public sphere. The car’s current status—a display at the Storyteller’s Hideaway Farm and Museum in Lyles, Tennessee—ensures that Cash’s playful, subversive sentiment continues to resonate with audiences who appreciate the car’s role as a canvas for cultural satire and social commentary. The song’s enduring appeal lies in its clever premise, its storytelling efficiency, and its ability to turn a workplace fantasy into a broader cultural joke that invites listeners to reflect on aspiration, resourcefulness, and the practical jokes one can pull with a dream in mind.

One Piece at a Time is a celebration of improvisation, cunning, and a certain defiance of corporate systems—an attachment to the idea that an individual can, through humor and ingenuity, reshape the world around him, including the very machinery that power a nation’s consumer dream. Cash’s distinctive voice adds a layer of moral satire to the track: the protagonist’s theft-from-the-assembly-line scheme is bold and cheeky, yet it is undergirded by a sense that the dream of owning a Cadillac is something worth pursuing, even if the means are unorthodox. This duality—playful rebellion versus the risk of moral compromise—captures a peculiarly American sentiment: the belief that ingenuity, grit, and a sense of humor can enable ordinary people to stand up to large, impersonal systems and still walk away with something that feels uniquely theirs.

The song’s impact extends beyond its narrative fun. It contributes to the broader corpus of car songs that use automobiles as vehicles for social commentary, memory-making, and character-driven storytelling. Cash’s track taps into a long-standing tradition in American music of using the car as a stage for personal myth-making, a tradition that recognizes how vehicles—whether ordinary or extraordinary—provide the space for imaginative exploration, risk-taking, and the celebration of a distinctly American sense of possibility. The comedic charm of One Piece at a Time—matched with Cash’s compelling delivery and the song’s clever, escalating chorus—cements its position as a lasting favorite in the canon of car-themed music, a track that invites listeners to celebrate resourcefulness, humor, and the enduring dream of a car that embodies a person’s own version of the American dream, built piece by piece, on the road of life.

Deadman’s Curve: tragedy, sensationalism, and the darker side of car culture

If there is a counterpoint to the celebratory car songs in this lineup, it is Deadman’s Curve, a track that blends infectious melody with a somber reminder of the perilous side of car culture. The collaboration behind Deadman’s Curve—Jan Berry of Jan and Dean, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, radio DJ Roger Christian, and songwriter Artie Kornfeld—created a song that is as catchy as it is cautionary. The narrative centers on a fatal drag race between a narrator in a Corvette and a challenger in a Jaguar, beginning at a red light on Sunset Boulevard and culminating in tragedy at a curve on the road. The record’s No. 8 peak on the Billboard Hot 100 attests to its resonance and the way it captured a public fascination with speed and risk, even as it warned of the costs that can accompany that thrill.

The darker arc of the Deadman’s Curve story takes a tragic turn in real life. On April 12, 1966, Jan Berry’s own life intersected with the song’s narrative when he crashed his Corvette into a parked truck near the curve, suffering a head injury that left him with lasting brain damage. He would later regain some function and perform again, but the injury strained his partnership with Dean Torrence, and the two did not share the stage again until the late 1980s. The juxtaposition of the song’s fictional drag race with Berry’s real-life accident created a luminous, cautionary parable about the seductive pull of speed and the vulnerability that even the most skilled performers carry within them. The tragedy of Berry’s accident—paired with the song’s cautionary premise—permanently linked Deadman’s Curve to the moral complexity of car culture: speed can be exhilarating, but it also demands responsibility, and the line between performance and peril can be perilously thin.

Deadman’s Curve stands as a stark reminder that the car as a symbol can represent not only liberation, romance, and social status but also risk, mortality, and the fragility of the human condition in the face of modern machines. The track’s enduring appeal lies in its infectious groove, its bright harmonies, and its capacity to tell a story of desire and danger simultaneously. The juxtaposition of the fun, celebratory sound with the grave undertone of a real-life accident underscores a core tension within car culture: the dream of speed and the reality of consequences. The song’s legacy endures because it refuses to sanitize the risks of the road, instead inviting audiences to reflect on the kinds of choices that can define a life on the edge of velocity. It’s a reminder that car songs can be both entertainment and ethical meditation, using melody to navigate the fine line between thrill and tragedy.

The broader mosaic: how these seven tracks define a car-song canon

Together, these seven tracks form a durable mosaic that illustrates how car-themed music has evolved from playful celebrations of cruising and style into nuanced meditations on desire, identity, and social critique. The Beach Boys helped crystallize a youthful revelry in speed and sun-drenched imagery, while the era’s other artists seized on the same photographic material to tell more complex stories. Janis Joplin’s Mercedes Benz issued a stark counterpoint to glamour, using minimal sound and provocative lyricism to interrogate materialism and spiritual longing. Prince’s Little Red Corvette interrogated romance’s risk-laden terrain through a car‑as‑metaphor lens, and its real-life inspiration in a pink Mercury Montclair adds a layer of backstage color to the song’s myth. Cadillac Ranch, with its art-world desert iconography, elevated the vehicle to a symbol of national myth-making and consumerism, while the Pontiac GTO track anchored the car’s cultural currency within the burgeoning muscle-car era and the social currency of performance driving. Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time added a heist-humor sensibility to the canon, model sharing, and the idea that a dream can be built piece by piece, even if the method is irreverent. Deadman’s Curve offered a cautionary tale about risk and mortality on the road, reminding listeners that speed can be both thrilling and deadly.

This constellation of songs exemplifies how auto-themed music can serve multiple purposes within pop culture. It can function as nostalgia, cultural critique, social commentary, or personal storytelling, all while maintaining a strong sensory appeal rooted in car imagery. The seven tracks together demonstrate a broad tonal palette—from exuberant, up-tempo celebration to wry, satirical commentary and to somber, cautionary ballads. In many ways, the car becomes a character in its own right across these songs: a symbol of freedom, wealth, experimentation, and escape; a stage for romance, risk, and social performance; a reminder of mortality; and a canvas upon which artists can project communal memory and personal longing. The enduring appeal of these songs is not simply in their catchy hooks or their production tricks; it lies in how they capture the social and cultural texture of their times—how Americans imagined themselves on the road, what they believed a car could do for them, and how those beliefs were shaped by the music that accompanied every mile.

Readers who listen closely will notice the thread of a shared myth: the car as a gateway to a wider world—romance, adventure, and opportunity—while also acknowledging that such gateways come with costs. The collection avoids a single, uniform narrative about cars; instead, it presents a series of intersecting experiences—some celebratory, some cautionary—that collectively chart the cultural arc of cars in American music. The stories behind these songs—from spontaneous bar-room improvisations to meticulously crafted hit records, from studio lore to the public’s enduring fascination with prototypes like the GTO or the Thunderbird—demonstrate how car culture has remained a core ingredient of American pop storytelling. The result is a rich, textured panorama of musical car lore that continues to resonate with listeners who are drawn to the allure of speed, the drama of the road, and the ways in which automobiles reflect—and shape—our collective aspirations and anxieties.

Conclusion

The seven car songs explored here illuminate how vehicles have served as more than mere backgrounds for popular tunes. Each track uses the car as a catalyst for storytelling, social commentary, or cultural mythmaking, turning engines and exhaust into symbols of freedom, aspiration, desire, and even danger. From the Beach Boys’ sunlit celebration of cruising life to Janis Joplin’s bar-room indictment of materialism, from Prince’s flirtatious, metaphor-filled masterclass to Springsteen’s desert tableau of the American dream, and from the GTO’s muscle-car anthem to Cash’s FrankenCadillac fantasy and the deadly caution of Deadman’s Curve, these songs collectively define a durable, multi-faceted canon. They reveal how the car’s meaning has shifted over time—from playful gadget to symbol of power, from social rite to personal myth—and how music has captured and circulated those shifts with remarkable staying power. In the end, car songs endure because they are about more than speed; they are about the journeys we take, the myths we chase, and the ways we imagine ourselves on the world’s longest, most treacherous, yet temptingly open road.