A cultural crossfade between chrome, horsepower, and rock ’n’ roll has long defined a distinctly American soundtrack. From the mid-20th century onward, cars and songs collided to celebrate freedom, rebellion, and the open road. The Beach Boys’ early-1960s car anthems helped anchor this fusion, while later generations found new ways to fuse motor imagery with musical storytelling. This piece revisits seven defining car songs and the moments, people, and mythologies that propelled them into the cultural bloodstream. It’s a journey through nostalgia, design, ambition, and the enduring allure of the automobile as a symbol of both escape and aspiration.

Fun Fun Fun

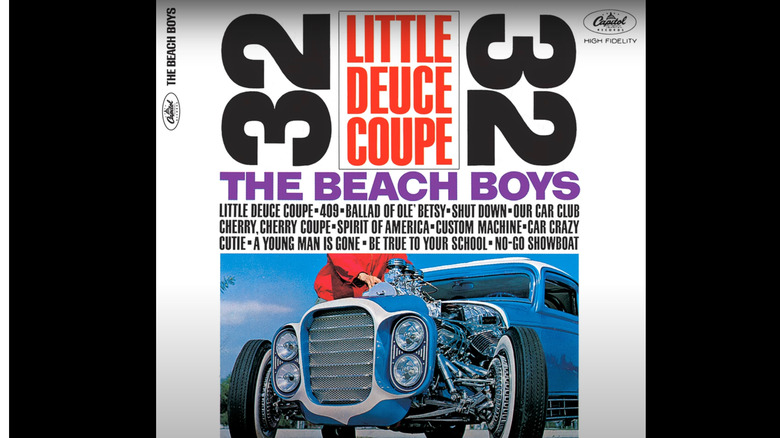

The Beach Boys’ lineage as the planners and heralds of the car-songs movement is inseparable from the period when muscle cars and rock ’n’ roll rose together to redefine American popular culture. In the wake of their 1963 album Little Deuce Coupe, which was saturated with car-themed tracks and became a chart phenomenon in its own right, the band demonstrated how deeply entwined cars were with youth culture, cruising, and sonic experimentation. The title track of Little Deuce Coupe not only resonated with listeners but also helped anchor a broader trend: turning specific car models into portable, portable culture capsules—symbols that could ride across radio airwaves as easily as they could roll down a sunlit boulevard.

The Beach Boys were not the sole torchbearers of this movement, but their contribution is pivotal. The 1963 album enjoyed notable commercial success, peaking at a high position on the album charts and maintaining a lengthy presence in the top tier of the charts. The broader arc of car songs in this era included a roster of artists who found in automobiles a potent metaphor for freedom, romance, danger, and the excitement of youth. Within this horizon, Fun Fun Fun emerges as a quintessential track that compresses the excitement of a night out into a lively musical narrative. It captures a girl who tears through the streets in her father’s Ford Thunderbird, signaling a break from strict parental oversight and the broader social codes that governed young people’s behavior at the time.

The narrative arc of Fun Fun Fun extends beyond the narrative itself. The first studio session for the subsequent album, Shut Down Vol. 2, produced this upbeat, propulsive statement that became a staple in the Beach Boys’ live performances for decades. The song’s rhythm, tempo, and hook-like chorus invite immediate participation—an instinctive urge to tap a foot, sing along, and visualize the era’s cruising culture. The imagery embedded in the lyrics and the album art creates a vivid snapshot: a teenager’s nightlife framed by a Thunderbird’s silhouette, with the social ritual of cruising and the promise of independence that comes with driving as a rite of passage.

Lyrically, Fun Fun Fun leans into a playful, almost cinematic depiction of 1960s cruising and the social rituals around cars. The chorus encapsulates a sense of defiance and exuberance: a carefree declaration of “fun” that is both a personal celebration and a challenge to conventional rules. The song’s cultural footprint endures; it remains a fixture in the Beach Boys’ live sets and in the broader canon of car-centric pop-rock, illustrating how automobile imagery can elevate everyday experiences—driving, stopping for burgers, racing and spectacle—into a universal, enduring mood. The track’s subject matter—an explicit focus on a Thunderbird—also echoes the era’s fascination with design and style as extensions of personal identity.

The interplay between the song’s narrative and the era’s automobile culture is further enriched by the album’s visual storytelling. The album cover on which the members are poised with what appears to be a Chevrolet Corvette and a Pontiac GTO reinforces the era’s fascination with American-made performance and the aspirational appeal of European styling, even as the band’s own identity remained rooted in Southern California sun and surf. The tension between the explicit reference to the Thunderbird in the lyrics and the visual cues presented in the album packaging reflects a broader cultural phenomenon: the car as symbol, as fashion, and as an instrument of social signaling.

The song’s lyricism also captures a broader texture of the time—portrayals of casual rebellion and the social rituals of the 1960s. The imagery of hamburger stands, street racing, and the social ritual of cruising life convey a sense of place and moment, turning a car into a stage for social interaction. The enduring appeal of Fun Fun Fun can be traced to its infectious energy and its capacity to translate a youth culture’s enthusiasm for mobility into a pop music form that invites participation, movement, and shared experience. The track’s legacy sits at the intersection of performance, design, and social behavior, illustrating how a car song can crystallize a generation’s relationship with machines, freedom, and communal experience.

As a cultural artifact, Fun Fun Fun stands as more than a catchy tune. It is a lens into a period when car culture and rock music aligned to produce a lasting resonance that continues to inform how car songs are composed, performed, and perceived. The tune’s propulsion and its sense of momentum deny stagnation; it invites listeners to imagine themselves in motion, cruising down a sunlit avenue, lights gleaming, and the night ahead full of promise. In this way, the track contributes to the broader narrative of car songs as a living genre, continually reinterpreted by artists across generations.

The broader lesson of Fun Fun Fun is the demonstration that a specific car model can function as a narrative device—an emblem that anchors lyrics, mood, and social context. While it centers on the Thunderbird and signals a particular moment in American car design, the song’s essence transcends model specifics. It captures the joy, risk, and thrill of youth behind a wheel, the social dynamics of a new era, and the enduring appeal of a great chorus that makes audiences want to clap along, tap their feet, and dream about the next road ahead.

The track remains a touchstone for fans and musicians who seek to explore the relationship between cars, music, and cultural identity. Its continued presence on stage and its continued relevance in the broader canon of auto-themed songs underscores how a well-crafted car song can endure far beyond its original period, continuing to resonate with new listeners who encounter it in a different social and technological landscape. Fun Fun Fun thus stands as a foundational piece within the car-song conversation and a testament to the Beach Boys’ lasting imprint on American popular music.

Mercedes Benz

The genesis of Mercedes Benz, a song by Janis Joplin that stands apart from other car-centered tunes, is rooted in a spontaneous, almost improvisational moment that became a stark critique of materialism and a meditation on human longing. The narrative traces back to a late-1960s crossroads where a lyric fixation met a fleeting idea that grew into a stark a cappella performance, then into a studio-era artifact tied to an album project and a performer whose life was as dramatic as the music she recorded. The origin story of Mercedes Benz is as much about the people in the room as it is about the words themselves. A conversation among friends in a Port Chester bar, with the poet Michael McClure contributing a line, set in motion a creative spark that found its way into the hands and voice of Joplin, whose ascendancy and untimely passing would only sharpen the song’s mythic status.

On a warm August night, the scene unfolds with Joplin and her associates, including Bob Neuwirth, gathered in an intimate bar setting. The origin line—an audacious, almost intimate plea to a higher authority—became the seed from which the song grew. The autoharp came into play, a tool that added a spare, stark texture to the piece, emphasizing the raw, unadorned vocal delivery that would become a signature of the performance. The atmosphere of the moment—spontaneous, intimate, and candid—transformed into a track that would be recorded toward the end of Joplin’s Pearl era, capturing a moment of artistic risk and vulnerability.

The recording of Mercedes Benz took place as part of the album sessions later that year, during a period that would soon be shadowed by Joplin’s death. The song emerged as a counterpoint to more polished studio work, presenting a stripped-down, stark a cappella presentation that relied on the power of voice, breath, and minimal accompaniment to convey its message. It is often noted that the piece was not originally intended for release; it was a barroom experiment that somehow found its way into the production process and into history, where it stands not as a celebration of wealth or luxury, but as a pointed critique of materialism and a call for humane, personal recognition beyond the cycle of consumption.

The lyric center of Mercedes Benz challenges conventional car culture’s symbols of success. Rather than an ode to a particular model or an emblem of status, the song uses car culture as a foil for existential questions about love, generosity, and the desire for meaning in a world of consumer excess. The famous refrain, entreating for a night on the town that is purchased rather than earned, casts a satirical light on the social rituals surrounding desire and wealth. The piece transcends its immediate context by inviting listeners to reflect on what constitutes value and how personal connections might outpace the pursuit of status symbols, even as the imagery remains inextricably linked to cars and the social rituals that revolve around them.

A notable detail is the song’s title itself. Mercedes Benz signifies luxury, engineering prowess, and the allure of a brand that epitomizes a particular aspirational lifestyle. Yet the song’s content deliberately subverts that association, turning the luxury badge into a rhetorical device for examining material cravings and the emptiness that sometimes accompanies it. The line of the song—delivered in a voice that is both fragile and defiant—functions as a social critique and a personal confession, inviting listeners to question what they would do if money, status, or access were the only means of fulfilling longing. The track’s brevity, starkness, and emotional directness create a powerful counterpoint to more expansive, production-heavy work of the era, making Mercedes Benz a standout in Joplin’s catalog and in the broader canon of car-related songs that ventured into more experimental and contemplative territory.

In the arc of car songs, Mercedes Benz represents a pivot away from celebration toward introspection. It is less a tribute to a specific vehicle than a meditation on modern life’s demands and the hunger for affection and human connection in a world that often equates worth with ownership. The piece’s historical context—recorded in the late-1960s and released posthumously—adds layers of poignancy to its interpretation. While cars as a symbol of freedom and power are still present in the music, Mercedes Benz uses that symbolism to critique how the pursuit of luxury can obscure more meaningful forms of engagement and generosity.

The song is also notable for its place in the verse of Joplin’s repertoire. It sits alongside other late-era studio explorations that sought to break conventional arrangements and present raw, unfiltered emotion. The performance’s starkness makes it a masterclass in how to convey complex ideas with minimal musical scaffolding. The narrative and the emotional arc of Mercedes Benz thus extend beyond its surface as a car-themed piece; it becomes a philosophical meditation on value, desire, and the human need for connection that transcends material wealth. In its compact, unadorned form, the song powerfully communicates these ideas and remains a defining moment in the intersection of car culture and singer-songwriter expression.

Prince’s Little Red Corvette is another transformative entry in this car-song landscape, though its relationship to “the car” is more symbolic and metaphorical than literal. The track, while anchored in the concept of a car—a Corvette in the title—reaches beyond that concrete image to explore themes of desire, velocity, and the complexities of romance and sexuality within the social codes of the early 1980s. The song’s origins, as recounted by members of Prince’s circle, reveal a moment of creative improvisation and storytelling that ties a personal, intimate moment to a broader commentary on performance, appearance, and longing. The mythic imagery surrounding a red Corvette gives way to an exploration of virility, impulse, and the navigation of intimate relationships within a culture fascinated by speed, risk, and the allure of high-status symbols.

A key anecdote that surfaces in reflections on the track concerns the back seat moment that sparked the idea for the song. A Pink Mercury Montclair, owned by a band member’s acquaintance, becomes a symbolic stage on which a scene of romantic intoxication unfolds. The memory of a private, shared moment in a car translates into a song that uses car imagery as a metaphor for desire and social performance. The lyric content, carefully parsed, signals that the connection to a car is not a literal depiction of a vehicle’s features but a vehicle for exploring power dynamics, attraction, and the thrill of pursuit. The track thus becomes less about the car’s model and more about the symbolic space the car represents—one of secrecy, possibility, and the tension between public performance and private longing.

While the track’s title and its references to a Corvette might lead some listeners to expect a celebration of a particular vehicle, the underlying narrative points to broader themes. The music video and subsequent anthologies and greatest-hits collections have reinforced the track’s status as a cultural touchstone for virility and ambiguity around sexual relationships. The song has become a cultural shorthand in popular discourse, evoking speed, risk, and the intoxicating energy of a moment when desire surges and consequences become secondary to the exhilaration of the ride. The Pink Mercury Montclair anecdote also illuminates the way Prince drew inspiration from real-life experiences and the social environments around him, transforming these moments into a broader commentary on love, power, and the performance of identity.

In many ways, Little Red Corvette sits at a crossroads of musical experimentation and cultural critique. It demonstrates how a car-themed song can function on multiple levels: as an anecdotal origin story, as a vehicle for exploring intimate relationships, and as a metaphorical exploration of velocity and control in social life. The track’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to combine an alluring, seductive mood with a sharper, more reflective inquiry into the dynamics of desire, the performance of masculinity and glamour, and the complexity of human relationships under the gaze of a fast-paced culture. The result is a track that remains both a quintessential early-1980s pop artifact and a timeless statement about the ways in which cars—beyond their mechanical purpose—serve as vessels for storytelling, identity formation, and social aspiration.

Cadillac Ranch is a Bruce Springsteen classic that opens a window into the aural universe in which cars act as vessels for memory, aspiration, and historical reflection. Springsteen’s body of work is enriched by a recurring theme: the romance of the road, the sense of possibility that a car represents, and the ways in which mobility becomes a metaphor for personal and collective journeys. On The River, a double album released in 1980, he anchored several car-themed songs alongside other tracks that examine the moral and social complexities of life in modern America. Cadillac Ranch stands out as a high-octane anthem within this discography, weaving a tapestry of automotive imagery that resonates with the era’s fascination with speed, design, and the cultural significance of cars.

The lyric imagery in Cadillac Ranch leans into a celebration of automotive aesthetics and the social rituals that surround cars in American culture. References to classic car features such as Eldorado fins, whitewalls, and skirts conjure a vivid image of 1950s and 1960s styling, while drawing a line to iconic film and television moments that embed these visuals in the public imagination. The track’s nods to cultural touchstones—James Dean with his notorious era-defining car, Burt Reynolds and the Trans Am in the road-film canon—create a mosaic of mid-century American identity. The Cadillac Ranch installation near Amarillo, Texas, becomes more than a visual artifact; it is a social and artistic phenomenon built on the premise of aspirational wealth and the dream of cruising freedom that cars symbolize for generations.

The Cadillac Ranch in real life adds another layer to the song’s meaning. Commissioned in 1974 by Texas artist Stanley Marsh 3, the installation features ten Cadillacs buried nose-first in the desert, serving as a provocative public art piece that invites contemplation of postwar American ambition and the language of luxury. The use of Arabic numerals in Marsh’s name—eschewing Roman numerals—signals a playful instinct for disruption, a willingness to challenge established forms and conventions. The installation’s ongoing evolution, including repainting and graffiti over time, captures the dynamic, living conversation between art, commerce, and public space. Marsh described the Cadillac Ranch as a monument to the American dream, a sentiment that sits at the core of the car-as-symbol discourse that Springsteen’s song contributes to and amplifies.

The cultural significance of Cadillac Ranch is deepened by the connection to iconic images of automobility in American media. The song’s lyric and the installation’s public presence together conjure a sense of youthful rebellion, wealth, and the desire to “get away from home” that defined generations of drivers in the mid-20th century. The narrative invites listeners to see the car not merely as a device for travel but as a powerful symbol that can reflect personal ambition, social status, and the ability to shape one’s own future through mobility. In this sense, Cadillac Ranch becomes more than a track on an album; it is a converging point where music, visual art, and automotive culture meet to articulate a broader story about the American dream, its promises, and its fragilities.

The Pontiac GTO’s impact on car culture is inseparable from the way music started to celebrate the muscle-car era as a period of performance, power, and personality. The GTO—the product of the John DeLorean-designed Pontiac line—made its public debut in 1964 and catalyzed a wave of high-performance, street-ready cars that defined a generation’s driving experience. In the same year, a song titled G.T.O. emerged from Ronny Dayton and the Daytonas, quickly becoming a defining anthem of the era. The track—often misnamed as Little GTO due to its opening line—reached No. 4 on the Billboard Pop Singles chart and sold a million copies, solidifying the GTO’s cultural resonance beyond showroom floors and into the radio and home listening rooms of millions.

The song’s success can be attributed to its period-appropriate blend of swagger, technical detail, and memorable melodic hooks. It captures the appeal of a “tri-power” engine and a hot cam, with performance exhaust and a tireless sense of momentum that matches the era’s enthusiasm for speed and showmanship. The songwriter behind the piece, Ronny Wilkin, was part of a broader ecosystem that included a strong Nashville songwriting community and cross-pollination with country music. Wilkin’s background, and the fact that his mother, Marijohn Wilkin, was a prominent figure in the publishing world and a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, adds a layer of intergenerational mentorship and industry leverage to the story. The publishing structure that helped bring the song to audiences also reflects a broader ecosystem of songwriting, publishing, and performance in the 1960s that enabled car-themed songs to cross over from regional scenes into national consciousness.

Marijohn Wilkin’s influence on Ronny’s career extended beyond the specific song. She built a publishing platform that fostered a collaborative environment for songwriters and performers and broadened the reach of their work into mainstream markets. Her role in launching and supporting the song’s release highlights the interplay between songwriting, production, and distribution that defined the era’s music business. The narrative of G.T.O. thus becomes a case study in how a car-centric track could emerge from a specific assembly of talent and industry networks and then radiate outward to become a durable symbol of American car culture, one that continues to be revisited by audiences who recognize the GTO as a landmark of the muscle-car era and a defining musical moment that personified speed and style.

The broader significance of the Pontiac GTO in car-song history lies in its demonstration that a vehicle’s image can be elevated to a cultural icon through music. The song’s success illustrates the era’s fascination with the “tri-power” configuration and the sense of engineering prowess that the car signified to fans. It also reflects the collaboration among musicians, writers, producers, and publishing houses that created an ecosystem whereby a car model was not merely a product but a living symbol, capable of driving conversations about power, engineering, and the social cachet associated with performance vehicles. The GTO’s legacy, reinforced by the song, contributes to a larger narrative about how car culture and music co-create a language of aspiration, identity, and shared experience across multiple generations.

Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time offers a masterclass in combining humor, social critique, and automotive folklore into a single, memorable narrative. The track—crafted by Wayne Kemp and performed by Cash in the mid-1970s as part of his broader body of work that embraced the Outlaw Country ethos—tells the story of an employee on a Cadillac assembly line who, through a clever but imperfect plan, crafts a FrankenCadillac by stashing mismatched parts in a lunchbox and in a friend’s RV. The resulting car is a patchwork of design, models, and eras, a symbol of both ingenuity and audacious, if illicit, resourcefulness. The song’s clever conceit culminates in a reveal that blends humor with social observation—the image of a “60-pound” title and a vehicle that embodies a mishmash of postwar American car history.

The story’s cultural footprint extends beyond the song’s linear narrative. Promoters used the concept of the FrankenCadillac as a promotional tool, creating physical representations that brought the song’s idea into the real world and into public demonstrations of mechanical whimsy. The narrative’s appeal lies in its celebration of ingenuity, improvisation, and a certain rebellious cheekiness—traits that resonated with Cash’s broader persona and the outlaw-country mood he helped define. The car on display at events and in museums became a tangible artifact of popular culture’s fascination with cars as platforms for creativity, subversion, and storytelling. The song’s humor, coupled with its homage to craftsmanship and on-the-line improvisation, makes it a standout entry in the car-song genre, illustrating how a vehicle’s image can be reimagined through music as an emblem of resourcefulness and narrative play.

Beyond the humor, the track also highlights Cash’s willingness to engage with a broader cultural conversation about consumerism, labor, and the assembly-line-era reality of American manufacturing. By turning the factory process into a fantastical, almost childlike vanity project, the song invites listeners to reflect on the tension between mass production and personal invention. One Piece at a Time thus functions as more than a novelty tune; it is a commentary on the American industrial landscape, a place where a man could humorously imagine a dream machine built from a patchwork of era-spanning components, each with its own story and provenance. The FrankenCadillac’s enduring memory in music history underscores Cash’s ability to blend humor with social insight, offering a playful yet pointed critique of the era’s car culture that remains relevant to audiences exploring the genre’s broader themes of ingenuity, rebellion, and the relationship between labor, ownership, and identity.

Deadman’s Curve stands as one of the most poignant examples of a car-song’s capacity to mix upbeat mood with darker undercurrents. The track—originally a collaboration among Jan Berry, Brian Wilson, Roger Christian, and Artie Kornfeld—tells a vivid narrative of a drag race that ends in tragedy. Set on Sunset Boulevard, the song follows a narrator who races a Jaguar against a Corvette, and the dramatic conclusion arrives at a dangerous curb where the Jaguar’s driver loses control and perishes in a wreck. The song’s success on the charts—reaching a high position on the Billboard Hot 100—speaks to its immediate resonance with listeners who can visualize the glamour and danger of street racing, the bright lights, and the redemptive yet fragile sense of youth that defined the era’s car culture.

The real-world consequences surrounding the song’s creation add an additional layer of gravity to its narrative. Jan Berry, one-half of the duo responsible for Deadman’s Curve, would suffer a devastating car accident in 1966, involving a Corvette and a parked truck near the curve. The injury would impact his ability to perform, and it signaled a turning point in his career and in the trajectory of the duo. The accident’s timing, following a period of intense creative output, underscores the fragile link between art that celebrates speed and the real-world risks that speed can entail. The broader implication for fans and observers is the reminder that car culture, while often celebrated for its optimism and exhilaration, is also marked by tragedy and risk. The song’s fatalistic tone, even as it remains buoyant in mood, reflects the dual nature of car culture—the allure of velocity and the sobering potential consequences.

Deadman’s Curve thus occupies a critical place in the car-song canon. It is a track that encapsulates both the thrill and the peril of the driving experience and does so within a framework that includes collaboration between notable writers and artists who would later shape the broader cultural landscape of the 1960s and 1970s. The song’s enduring popularity is a testament to its dual ability to entertain with its catchy melody while also provoking reflection on the darker aspects of car culture. The narrative’s blend of celebration and cautionary note continues to resonate across generations of listeners, who recognize the allure of the open road and the need to approach speed with respect and awareness of its consequences.

In sum, Deadman’s Curve is not merely a nostalgic reminiscence of a bygone era’s road fantasies. It is a reflective piece that challenges audiences to consider the relationship between speed, artistry, and risk, and to acknowledge the human realities behind the gleam of chrome and the roar of engines. The track remains a definitive moment in the car-song lineage—a reminder of how songs can capture both the joy and the danger of the road, and how real-life events surrounding the music can deepen its emotional impact and historical significance.

The G.T.O. and the muscle-car era’s musical uplift

The Pontiac GTO emerged as a time-anchoring symbol of the American muscle-car era, setting a benchmark for performance, style, and cultural aspiration. Dramatizing the car’s birth and influence, the track about the GTO—often labeled as Little GTO in popular memory due to its opening line—captured the era’s appetite for speed and mechanical bragging rights. The car’s debut in 1964, under the John DeLorean-designed Pontiac umbrella, coincided with a powerful surge of enthusiasm for high-performance automobiles, and the year’s cultural weather was ripe for a song that could translate that energy into a musical anthem.

The song’s origin story, involving Ronny Dayton—an artist who operated under the moniker Ronny and the Daytonas—adds a layer of rapid, era-driven phenomenon. It became a major hit, achieving a top spot on the Billboard Pop Singles chart and selling a substantial number of copies, reflecting the era’s appetite for catchy, fast-paced melodies centered on a car’s allure. The tune’s sonic character—tight arrangements, brisk tempo, and a chorus that demanded attention—made it a natural fit for radio airplay and the growing audience for rock, pop, and crossover hits in the 1960s. The track’s fame also contributed to the GTO’s reputation as a symbol of the muscle-car era—an emblem of mechanical power, competitive spirit, and a modernity that could be enjoyed in the social spaces of cruising and car shows.

Understanding the GTO’s cultural resonance requires acknowledging the broader ecosystem that supported the song’s success. The era’s publishing, recording, and distribution networks enabled a car-centric track to travel from a regional novelty into a nationwide phenomenon. The song’s popularity was not only about the car model itself but about a larger cultural narrative that celebrated engineering prowess, personal identity expressed through automobiles, and the social rituals of the time—cruising, road trips, and the social signaling that accompanies high-performance cars. The musical emphasis on speed, performance, and youthful bravado spoke to a generation’s desire for excitement and the sense that a car could be a stage upon which one could carve a personal legend.

Beyond its immediate musical appeal, G.T.O. also underscores the way car culture intersects with memory and myth. A car can become a living artifact in the public imagination, a symbol that carries with it a particular era’s aesthetics, attitudes, and stories. The song’s historical footprint is thus not limited to its chart success or its impact on subsequent automotive marketing and pop culture. It also reflects the deeper human attraction to speed and the sense that, through music, people can relive the energy of an era in which car culture and popular music were in constant dialogue. The GTO track’s enduring presence in the canon of car-themed songs demonstrates how a single vehicle can catalyze a broader cultural conversation about power, design, and the social rituals of youth.

The GTO’s legacy in both music and automotive history continues to influence how audiences understand the relationship between vehicles and identity. The car’s image—its distinctive styling, its mechanical bravado, and its place in American popular imagination—has been reinforced by songs that celebrate its presence on the road. The track’s popularity shows how music can help to mythologize a car as a symbol of a broader cultural moment, a moment when engineering prowess and personal style fused to generate a sense of possibility and exhilaration. The GTO thus stands as a testament to how automotive and musical narratives converge to create enduring cultural artifacts that inform contemporary interpretations of both machines and the people who drive them.

Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time and Deadman’s Curve, along with the GTO track, together illustrate the breadth of the car-song landscape: a space where humor, tragedy, social critique, and tribute can mingle within a single musical tradition. The seven entries explored here—the Beach Boys’ Fun Fun Fun; Janis Joplin’s Mercedes Benz; Prince’s Little Red Corvette; Bruce Springsteen’s Cadillac Ranch; the Pontiac GTO’s musical tribute; Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time; and Jan Berry and friends’ Deadman’s Curve—offer a cross-section of car-themed storytelling that reveals how cars have served as a mirror and an engine for cultural evolution. The stories behind these songs and the cars they celebrate reveal a nuanced portrait of American life—its ambitions, its risks, its humor, and its enduring appetite for speed and freedom.

One Piece at a Time

Johnny Cash’s One Piece at a Time stands out within the car-song tradition for its satirical, yet affectionate, depiction of automotive assembly-line life and the imagination of an everyman who dares to dream big—even if the means are comic and illicit. The track, crafted by Wayne Kemp, tells the story of a Cadillac assembly line worker who, over time, accumulates a patchwork collection of car parts, stashing them away with a sense of mischief and a subtle critique of the automotive industry’s mass-production machine. The resulting FrankenCadillac is not a showroom specimen but a symbol of ingenuity and perseverance—the kind of creation that emerges when ordinary workers turn everyday objects into something extraordinary through resourcefulness and storytelling.

The narrative arc culminates in a humorous, almost slapstick moment of revelation: the patchwork car that owes its lineage to several year models becomes, in a sense, a meditation on ownership, labor, and personal triumph. The song’s humor—rooted in the idea of stealing and assembling car parts for a dream machine—transforms into a commentary on the human tendency to reinterpret material surroundings and to imagine new possibilities even within the constraints of a highly regulated, industrialized context. The humor thus serves as a vehicle for deeper social commentary, inviting listeners to consider how personal vision and improvisation can challenge the limits imposed by mass production and corporate control.

The FrankenCadillac’s real-world echoes add to the song’s enduring appeal. Promoters sought to harness the track’s imaginative premise by constructing a version of the car for promotional tours, a public demonstration of mechanical whimsy that bridged music, car culture, and spectacle. The project’s two iterations—the first built by a salvage yard owner and later a second attempt by another enthusiast—demonstrate how music can spur tangible, real-world artworks and experiences that extend beyond studio recordings. Cash’s response to these artifacts—travelling to perform in Welch’s home town and proudly endorsing the FrankenCadillac—reflects the performer’s affinity for playful creativity and his interest in encouraging community-driven projects that celebrate the lore of cars and the people who love them.

The story of One Piece at a Time also highlights the broader social dynamics of the music industry in the 1970s. Johnny Cash’s persona as an emblematic figure within Outlaw Country—combining a rugged authenticity with a keen sense of humor—made the song resonate with audiences who connected with his storytelling approach and his willingness to embrace unconventional subject matter. The song’s enduring attractiveness rests on its balance between a narrative that is clearly humorous and a deeper truth about the human desire to possess, to celebrate, and to rethink the objects around us. The FrankenCadillac then becomes a metaphor for this impulse: a vehicle that physically embodies a dream, while also serving as a reminder of the limitations and compromises that come with real-world production and ownership.

The track’s cultural resonance extends to the way it frames the automobile as a site of invention and identity construction. Cars, in this sense, function as accelerants for imagination, enabling people to visualize an alternative future built from parts of the past and emerging possibilities alike. One Piece at a Time invites listeners to think about the car as a tapestry of memory, aspiration, and community conversation—an artifact woven from the labor of many hands and the dreams of a single, determined individual. The song’s humor, paired with its underlying message about resourcefulness and creative engineering, reinforces the idea that car culture is not merely about speed and styling but about the stories we tell about the machines we build, modify, and carry with us along the road of life.

Johnny Cash’s narrative, and the FrankenCadillac’s broader cultural journey, also interacts with the era’s broader discussions about labor, manufacturing, and the changing face of American industry. The car, with its patchwork history, serves as a symbolic lens through which to examine the relationship between workers, technology, and production systems. The track’s lasting appeal lies in its ability to transform the everyday into something fabulous, reminding listeners that imagination has a way of turning constraints into opportunities and that a well-told tale about a car can cross genres, generations, and social boundaries. One Piece at a Time remains a cornerstone of the car-song lineage for its inventiveness, humor, and its successful weaving of industrial realities with a dream of personal achievement.

Conclusion

The seven car songs explored here—Fun Fun Fun; Mercedes Benz; Little Red Corvette; Cadillac Ranch; G.T.O.; One Piece at a Time; Deadman’s Curve—offer a panoramic view of how automobiles have influenced popular music, and how songs about cars in turn shape the way listeners understand the world of driving, design, culture, and identity. From the Beach Boys’ sunlit celebration of cruising and youth independence to the more reflective, critical, and even humorous portrayals across genres, the car remains a powerful symbol that travels across eras, preserving a sense of movement, possibility, and shared experience. These tracks reveal how music can capture a moment in automotive culture while continuing to resonate with new audiences who discover them in different contexts, reaffirming the enduring connection between cars and songs as a core thread in American popular culture. The stories behind these songs illuminate a broader narrative about how machines, music, and memory co-create a language of aspiration that remains relevant, evocative, and transformative to listeners who hear them on the road or in the heart of the city.